[ad_1]

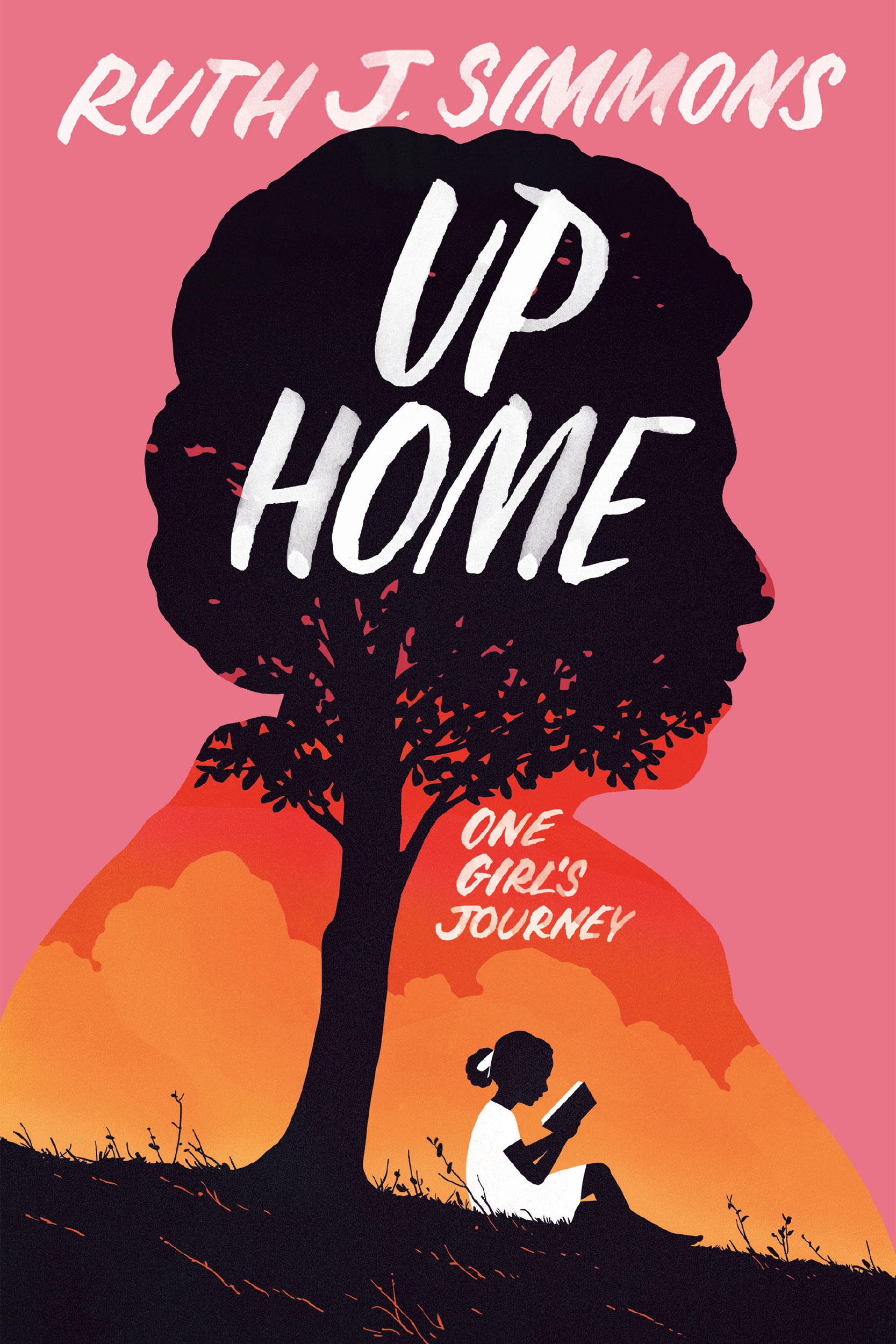

Excerpted from “Up Residence: One Woman’s Journey” by Ruth J. Simmons, Ph.D. ’73, LL.D. ’02, senior adviser to the president on engagement with Traditionally Black Faculties and Universities. Printed by Random Home, an imprint and division of Penguin Random Home LLC. All rights reserved.

A budget, wealthy soil of the Daly space in East Texas space inspired my maternal grandparents, Richard Campbell and Emma Johnson, to settle there within the Eighties. I’m left to think about what may have impelled the younger couple to set off from Mississippi with such a mission, however within the period of their exodus, the Southwest should absolutely have provided higher security and alternative for Blacks. Emma was born after slavery ended formally, and nothing is thought of the members of the family she left in Mississippi, as she by no means spoke of them. Richard got here initially from Virginia. He was born round 1870 to Martha Leonard and Andrew Campbell, each of whom had been slaves. Martha’s two boys, Doc and Richard, had totally different fathers, a proven fact that was obvious from their options. Doc was very darkish, and Richard was particularly reasonable. The Campbell boys steadily labored their method south to Mississippi, the place Richard met Emma and the three set off collectively on a ship for Texas. They landed in Oakwood, an East Texas city based in 1870 on the Trinity River, throughout from Daly.

After arriving in Oakwood, Emma and Richard quickly made their jump-the-broom marriage authorized by remarrying and recording their union within the Leon County courthouse. Their Holy Union of Matrimony occurred on August 19, 1891, 9 days after that they had secured their marriage license, with Reverend Frank Lloyd, an ordained minister, officiating. The identical “Minister of the Gospel” officiated when Doc married Bella Tryon, his second spouse, two years later. Collectively, in 1910, Richard and Doc purchased 60 acres of farmland situated 16 miles northwest of Crockett in Daly. The purchase, made collectively with their wives for $300, required diligent planning, saving, and no small quantity of ambition.

It’s straightforward to see why Richard, Doc, Emma, and Bella crossed the river to farm in tiny Daly, the place expansive cotton fields had been surrounded by crimson oak and put up oak timber and transected by creeks. And not using a city middle, the realm was house to homesteads massive and small that relied on close by Grapeland and different cities for a lot of wants. The absence of a busy city middle gave Daly a quiet, peaceable character in a setting of gently rolling hills and verdant, fertile fields. Even in the present day once I go to the realm, I’m shocked by the fantastic thing about the panorama, regardless of its deteriorating houses and farm constructings and overgrown fields.

My mom, Fannie Campbell, was born on this lovely land in 1906. She met and married my father, Isaac Stubblesubject, there and bore all of her youngsters inside just a few miles of her mother and father’ house. A loyal creature of this intimate landscape, she traveled solely to Grapeland, Oakwood, and, occasionally, county festivals within the area. For a lot of her life, she had solely horses and wagons as transport and, after our household acquired an vehicle, she by no means realized to drive. Her marriage additionally circumscribed her actions; she adopted the various relocations prompted by my father’s employment first as a farmhand and sharecropper and, later, as a laborer in Houston.

Right now, on the level the place the paved part of Route 227 abruptly modifications into hardened pebbly clay main towards Cedar Department, one other Grapeland-area group, a meandering climb to the left results in the highest of a cattle-grazed knoll the place a small, weather-worn home as soon as appeared out over the fields beneath. With no road addresses, homes and properties usually acquired the names of former homeowners or inhabitants. My father had moved our household to the home previously inhabited by Eddie Bryant, a neighborhood farmer, and there I used to be born after the tip of World Conflict II.

I’ve no private recollection of the Eddie Bryant home as a result of a few years after I used to be born our household moved to the Murray Farm, working the Murrays’ cotton fields. Betrigger I can drive from Grapeland to Daly in solely 10 or quarter-hour, the isolation of the Murray Farm and different websites in Daly once I was a baby is tough to think about in the present day. But, within the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s, round-trip journey from the realm to Grapeland and again would have taken the higher a part of a day, making it unattainable to go there with any frequency.

The Murray Farm was a village unto itself, with its personal comfort retailer and a sanctified church and faculty shut by. Sharecroppers sometimes purchased on credit score from the farm retailer, the place mounting indebtedness to the homeowners usually couldn’t be happy. I used to be too younger to pay attention to the dire financial components affecting sharecroppers. Like different families, we had a farm-owned home and a modest quantity of house for a backyard and chickens. These lodging met our fundamental wants. All sharecroppers loved the identical state and, having this in frequent, they often obtained alongside nicely and constructed friendships on the idea of their shared circumstances. We had been particularly near our nearest neighbors on the farm: Miss Lula Could, Miss Florida, and Miss Sis. Whereas I don’t recall understanding many sharecroppers, their colourful names continued to stay in household lore lengthy after we moved away, maybe as a result of they typified the proclivity of Blacks to present their youngsters names similar to Mr. Son, Child Woman, Mr. Junior, Mr. Brother, and so forth.

The church buildings in Daly had been the first social shops for Black sharecroppers. My father’s oldest brother, Elmo, helped set up Larger New Hope Baptist Church within the Nineteen Twenties, simply steps away from the Campbell 60 acres on Route 227. The constructing they erected was a rudimentary construction. The church stays in the present day a middle to which individuals return every year for “homecoming.”

Residence going and residential coming are essential ideas within the South, significantly in Black southern tradition. “Going house” may imply going to heaven after loss of life (as in gospel singer Mahalia Jackson’s magnificent non secular within the movie “Imitation of Life”), or it may merely imply returning to a rustic household’s ancestral house. Amongst my household and family from Houston County, “up house” is synonymous with Grapeland, however each household defines “up house” on the idea of their city of origin. I suppose if Grapeland had been south of Houston, we’d have mentioned “down house.” “Down house” additionally connotes a return to 1’s roots, to one thing that’s fundamental, homespun, or a easy evocation of the unique spirit of house, as in “down house” music or “down house” eating. I affiliate “up house” with the entire meanings and nuances of “down house.”

But in my early years I had no sentimental attachment to this space. I yearned as a substitute for distant, forbidden areas. Conscious that some had been shifting away from the realm, I receiveddered what their lives would possibly turn into elsewhere. I puzzled how shifting away would possibly form my very own life. As my older siblings relocated to Houston in quest of work, I appeared ahead to their letters telling of the world past the fields that I performed in. With no photographs from tv, films, or magazines out there, my creativeness was free to construct a whimsical world geography and picture capitals and folks in contrast to any I might later meet. Whereas in the present day’s youngsters are stimulated by a barrage of visible and auditory sensations from their very first second of life, we had nothing of the type.

Our stimulation got here partially from taking part in with and observing the pets and feral animals on our farm: canines and cats, birds and reptiles, squirrels and raccoons, horses and deer. Both they manifested distinctive personalities or we merely attributed distinctive traits to them. My father advised us tales that anthropomorphized “coons,” squirrels, foxes, deer, and different animals, however we additionally relied on our personal encounters with actual animals to maintain us amused.

Our house was abuzz with sounds of farm exercise, however what I loved most had been the various hymns that floated by means of the home and fields. These might be heard at any time of night time or day, and so they normally served as accompaniment for the various duties my mom carried out. She sometimes sang or hummed her favourite songs: “Previous Ship of Zion,” “Wonderful Grace,” “Jesus, Hold Me Close to the Cross,” and lots of negro spirituals. Singing was additionally a favourite pastime for others within the household. My sisters and I shaped a trio that pershaped in church, nonetheless a lot talked about and ridiculed by members of the family. Recollections of my singing invariably deliver gales of laughter.

Initially, Mama and Daddy had horses. We youngsters had been usually depending on our toes when the wagon was hauling cotton and horses had been in use pulling plows. Each playmates and adversaries, these horses usually entertained us with their outstanding personalities. For sport, Previous Dan, Daddy’s imply horse, would chase us, slobbering into our hair and tripping us. Mama’s horse, Minnie, disliked my father for some reason and she or he would provoke him. Someday my father was befacet himself with anger after Minnie chased him onto our porch. In a fury, he retrieved his shotgun from the home and hurried again exterior to finish Minnie’s days. Seeing my father with the gun, the horse loped away into the woods. Our bebeloved animals had been our salvation on the lengthy days when boredom usually took maintain.

After all, isolation was typically a bonus within the racially segregated and hostile world of Nineteen Forties Texas. Encounters with whites usually meant hazard. The hazard of not stepping apart as required when a white particular person handed. The hazard of wanting white folks instantly within the eyes and inexplicably offending them. The hazard of talking impudently or with an excessive amount of authority. The hazard of showing too proud. The hazard of being within the fallacious place. The hazard of overstepping well-understood boundaries. Within the presence of whites, one lived on edge as a result of any of them, regardless of their station, may summarily condemn a Black particular person to damage or punishment. So our mother and father urged us to look at the right conduct when encountering whites. And, out of worry, we did.

Racial mixing in a social context was taboo. My eldest brother, Elbert, a accountable and “mannerly” youngster, was usually admired by adults and given particular privileges due to his maturity. When invited to a white man’s home to listen to his daughter play the piano, Elbert thought of it a terrific honor, however as soon as he arrived on the massive white home in Grapeland he was advised, to his shock, that he couldn’t go inside; he must stand on the facet window to hear. His indignity was typical of the conduct of whites in that period. To ask a Black particular person into one’s house or church would recommend social parity, an inconceivable notion.

Interracial exercise in Grapeland was stuffed with such indignities. All establishments, in fact, had been segregated. Sepacharge church buildings, separate communities, separate social occasions, and separate seating had been ordained to forestall racial mixing. In the one native movie show, Blacks had been consigned to the balcony. Even locations on the streets and sidewalks had been earmarked for one or the opposite race. After that they had made their purchases and dropped their cotton on the native gin, Blacks sometimes gathered for recreation and socializing in an space on the facet of the overall retailer. No eating places had been out there to them, in order that they purchased meats and cheese and took their meal to that separate space to eat. Summer season sausage and saltines, cheddar cheese, and crimson “sodie water” had been a typical meal, with ice cream and sweet for youngsters. My favorites had been root-beer-flavored barrel sweet, coconut striped sweet, and peanut butter logs. The gathering website for Blacks was known as “buzzards’ roost.” To many white folks in Grapeland, we had been a bunch of crude Blacks who reminded them of a flock of buzzards, gathering to feed on leavings and detritus. We swooped in, circled, got here down for a feeding, and, as soon as we had our fill, moved on till the subsequent feeding.

But racial mixing did happen. A few of the Blacks and whites who handed one another on the streets had been blood family members. We didn’t acknowledge this truth overtly, however in a small city the reality was inescapable. Typically household bonds had been privately acknowledged as whites visited their Black family members within the latters’ houses and neighborhoods, however by no means within the white family members’ houses. The proof of miscegenation was someoccasions plain to see within the Black faces that abruptly turned away to keep away from being mistaken for “uppity niggers.” My father’s mom, Flossie Beasley, was associated to one among Grapeland’s founding households. She was the granddaughter of Liza, a slave, and Jim Beazley, a white man. Although the spelling of the surname modified, Flossie’s truthful pores and skin and straight hair, mixed with different options, made her ties to the white Beazleys starkly evident. This historical past was not as well-known to us as youngsters, however adults accepted it as a manifestation of the pathos and hypocrisy of racial segregation.

Regardless of these circumstances, I grew up with little resentment of white privilege. Though my siblings and I set different expectations for ourselves, my mother and father didn’t seem to simply accept greater than what was dealt them. Seemingly accepting the truth that that they had no energy to alter their circumstances, they largely loved their lives in rural East Texas. On my uncommon forays into Grapeland, I noticed the therapy my mother and father and their mates acquired. These had been my first lessons within the limitations folks assemble that may so simply denigrate human value and poison relations between races. On the first alternative, most of the “buzzards” so mistreated by the city would go away Grapeland, taking with them to new lives a big measure of the humiliation that had been inflicted upon them throughout their time in Houston County.

To be born in an atmosphere through which one is legally designated subhuman is a defining expertise. Fixed assertions that one is much less deserving of fundamental human and civil rights can turn into deeply ingrained, dominating one’s self-image and blocking the need to pursue formidable objectives or categorical one’s true identification. I’ve steadily been advised by whites that Blacks have “a chip on their shoulder.” They usually say this as whether it is ridiculous to have been marked deeply by the violation of 1’s human dignity and rights. It’s true that ideally we should always not allow even probably the most heinous circumstances to mar completely the course of our considering and our lives, however we should always not neglect that such an excellent is extra a fascinating purpose than a straightforward accomplishment. Residing one’s life throughout and after the violation of 1’s humanity is a take a look at and process that any would discover difficult, and it may be, as a minimum, an arduous lifelong pursuit.

Though I didn’t by any means witness firsthand the worst of what my mother and father and the remainder of my household experienced in Grapeland, I used to be definitely made conscious that being Black enclosed me in an online of stereotypes, which I might unlikely escape. I had no thought that I might be exempt from the therapy my mother and father recounted from their previous. To keep away from being overtaken by the circumstances I had inherited, I needed to think about the world as a much more fascinating and logical place, a lot as one would possibly stubbornly construct a citadel within the sand, understanding that will probably be washed away. However I by no means anticipated my imagined castles to switch completely the truth of rural East Texas within the ’40s and ’50s.

Right now, I personal the land that my mom inherited from her mom. As soon as married, Mama by no means once more lived on this land; she adopted the strikes and inhabited the houses dictated by my father’s employment. Although undeveloped, this land is value my proudly owning as a result of it represents the strivings of the Campbells and Stubblefields and the deep and willful connections that Mama and Daddy made to one another and the area. I return to the crimson clay roads and sandy fields of Daly as usually as I can to remind myself what I realized there: the necessity to stretch past the boundaries imposed upon me as a baby. I return to marvel at how my curiosity in far totally different worlds was kindled as I wandered barefoot by means of the sphere and meadows. I return to ponder what my grandparents Emma and Richard, and my mom and father will need to have endured to maintain us secure and to instill in us a way of self-worth within the face of colossal limitations to delight and accomplishment. And so, I maintain on to this land as a result of “up house” is a journey I’ll at all times make and “down house” is a sense I’ll at all times relish.

Copyright © 2023 by Ruth J. Simmons

[ad_2]