[ad_1]

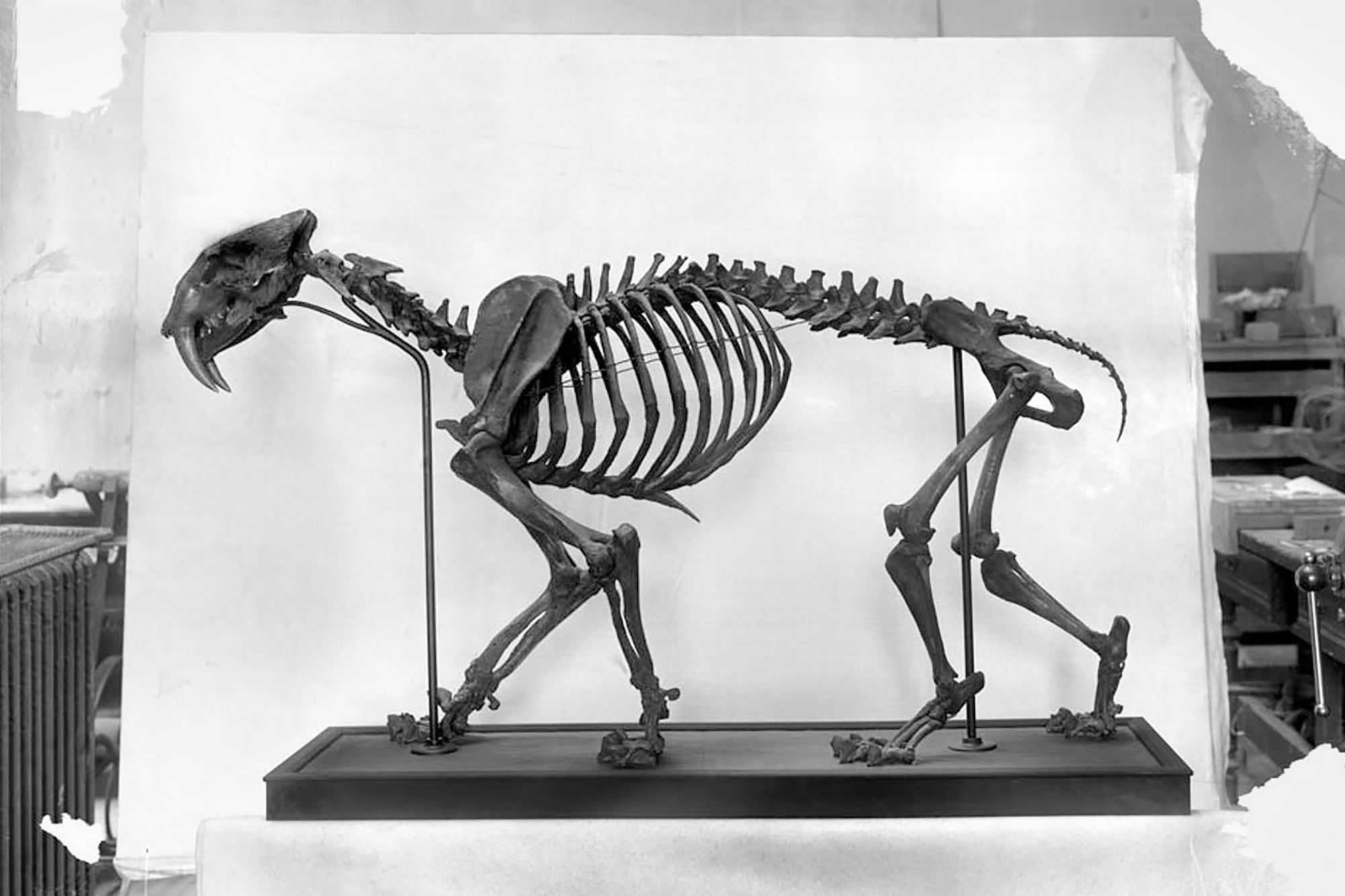

Some 14,000 years in the past, downtown Los Angeles was awash with dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, almost one-ton camels and 10-foot-long floor sloths. However within the geologic blink of an eye fixed, every little thing modified. By simply after 13,000 years in the past, these large animals had all disappeared. What have been as soon as lush woodlands had change into a dry, shrubby panorama referred to as a chaparral, and enormous fires have been widespread. What went fallacious?

Attainable solutions to that query come from new analysis into the famed La Brea Tar Pits printed on August 17 in Science. Between 50,000 and 10,000 years in the past, naturally occurring asphalt in these “tar pits” trapped organisms starting from huge predators to hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis). The brand new examine reveals simply how rapidly the biggest animals disappeared from the La Brea fossil document.

The researchers dated 172 specimens belonging to seven extinct species—the dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus), the traditional bison (Bison antiquus), a camel referred to as Camelops hesternus, a horse referred to as Equus occidentalis, the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis), the American lion (Panthera atrox) and Harlan’s floor sloth (Paramylodon harlani)—and the still-living coyote (Canis latrans). The scientists seen that though the coyote fossils dated anyplace from 16,000 to 10,000 years in the past, each different species abruptly disappeared someday between 14,000 and 13,000 years in the past, with the camels and sloths seemingly blinking out just a few hundred years earlier than the predators.

“Nobody within the examine was ready for what we discovered,” says F. Robin O’Keefe, a biologist at Marshall College and a co-author of the brand new analysis. “The coyotes maintain being deposited, however the megafauna simply, poof, disappear. And for many of them it is sort of a ‘poof’—it’s a fairly dramatic occasion.”

To attempt to perceive the destiny of those mammals, O’Keefe and his colleagues analyzed sediment cores from a close-by lake that offered information on air temperature, salinity and precipitation. The researchers have been significantly struck by a 300-year-long interval of excessive charcoal accumulation from wildfires within the lake that started about 13,200 years in the past—proper round when the megafauna went lacking from the tar pits. “We see these large pulses of charcoal going into Lake Elsinore unexpectedly, they usually’re monumental, in comparison with something that occurs earlier than that point or after that point,” O’Keefe says. “That’s what clued us in to ‘Okay, the fires are a very essential issue.’”

Subsequent the scientists used a pc mannequin to determine how fires, local weather change, species loss and human arrival within the space match collectively. And the result’s a way more sophisticated image of the extinction than that depicted by earlier theories, which frequently blame the extinctions on only one perpetrator, similar to human looking or local weather change. As a substitute, O’Keefe says, people seemingly pushed the ecosystem over the brink by killing off herbivores, which allowed the vegetation that served as wildfire gasoline to proliferate simply because the local weather was drying out anyway and left carnivores with out prey.

“It’s not essentially like huge wildfires drove an extinction of megafauna,” says Allison Karp, a paleoecologist at Yale College, who was not concerned within the new analysis. “It’s that human dynamics modified the fireplace regime; this interacted with a local weather that’s arid and at a better temperature; and this, mixed with decreases in herbivore densities, actually pushed the system in a nonlinear manner and shifted it to a different state—a state that included so much much less herbivores and a really completely different vegetation neighborhood and a a lot larger fireplace regime than had been seen beforehand.”

Jacquelyn Gill, a paleoecologist on the College of Maine, who was additionally not concerned within the new work, was not shocked that O’Keefe’s workforce discovered such a nuanced rationalization. “We all know that in fashionable programs, extinction could be very not often unicausal,” Gill says. “You usually have to have some drive that’s stressing this inhabitants. Then there’s usually a component of unhealthy luck or another stressor that is available in. We see that time and again.”

O’Keefe, Karp and Gill agree that the parallels between right now’s headlines and the disappearance of those iconic animals from southern California in opposition to a backdrop of wildfires and local weather change are eerie.

O’Keefe notes that the analysis traces a shift from two completely different ecosystems in only a few centuries. “Mathematically, it’s a disaster,” he says. “If the medium of that state shift is fireplace, and then you definately go searching, and every little thing’s beginning to catch on fireplace, you begin to suppose, ‘Is it taking place once more?’ That’s a rational factor to suppose.”

Understanding how extinctions unfolded way back, Gill says, may assist ecologists higher predict what would possibly occur subsequent right now. In that manner, they’ll predict which species, if left to their very own gadgets, usually tend to go the way in which of the dire wolves or that of the coyotes. “Ecologically talking, there are winners and losers each time we’ve got these huge upheaval occasions,” Gill says. “That data helps us to carry out the mandatory triage that we have to do as we attempt to save one million species.”

[ad_2]