[ad_1]

Life | Work is a collection centered on the private aspect of Harvard analysis and instructing.

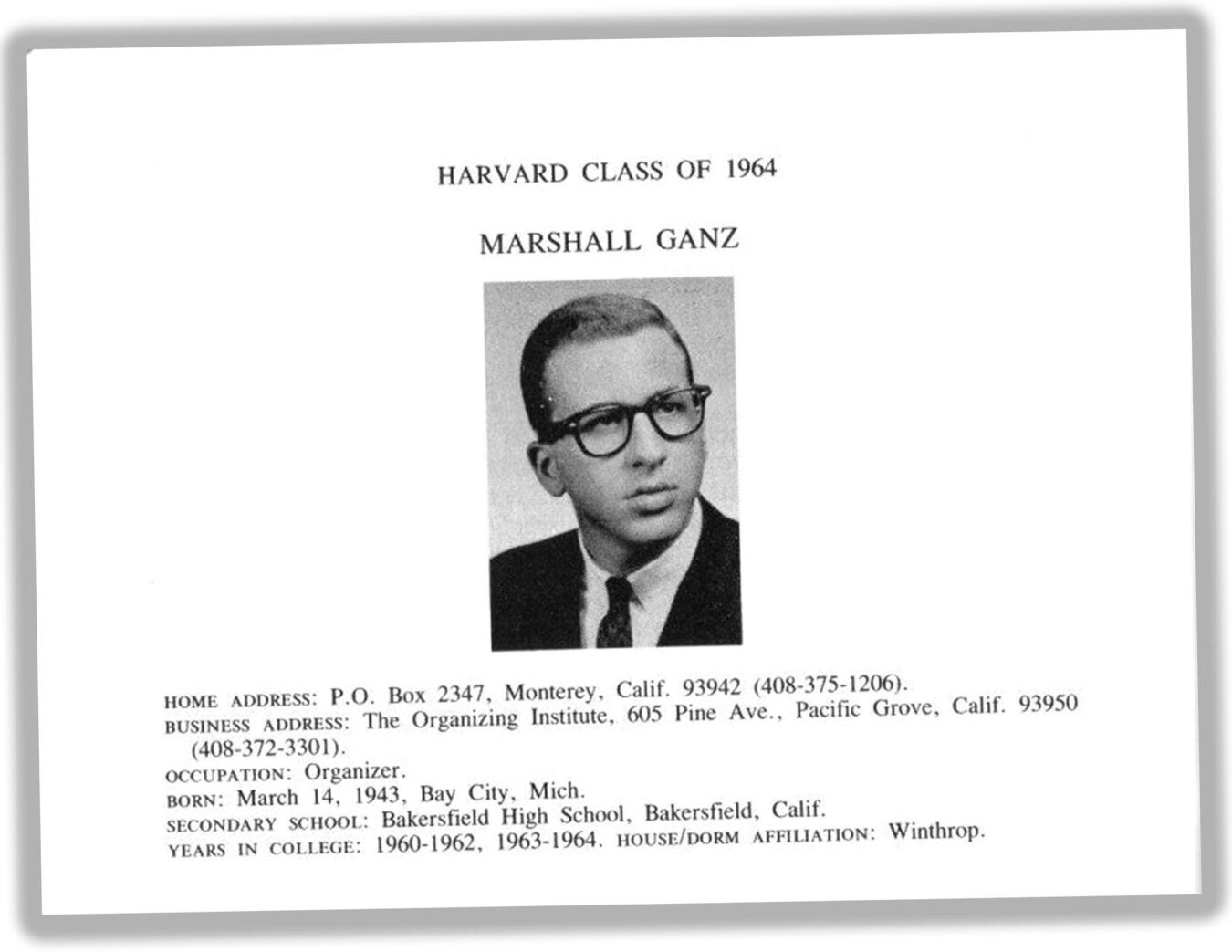

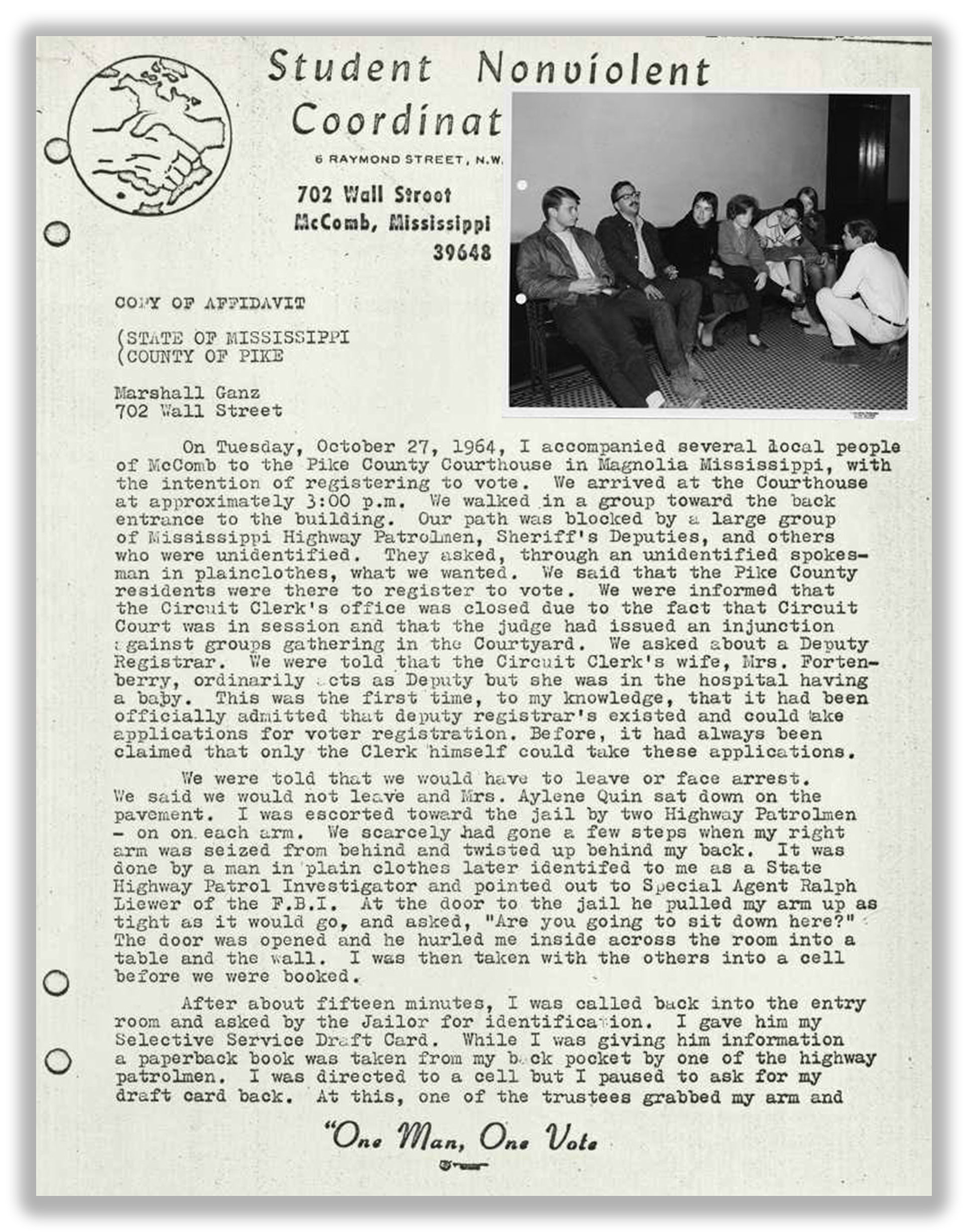

Marshall Ganz was a junior at Harvard Faculty, nonetheless struggling to determine what he needed to review and do along with his life. Then got here that tough, harmful — and exhilarating — Freedom Summer season of 1964 working with Civil Rights activists underneath the recent Mississippi solar to register Black voters, even being arrested twice and thrown in jail. His path turned clear.

“There’s a distinction between discovering a calling and a profession,” stated Ganz, Rita E. Hauser Senior Lecturer in Management, Organizing, and Civil Society at Harvard Kennedy Faculty, of his expertise. “How that was going to play out, and if it was going to maintain [me], who is aware of? The alternatives I made had been all the time, ‘What’s it that’s compelling to do proper now?’”

That galvanizing summer season led to an nearly 30-year break from the Faculty for Ganz, who labored as an organizer with the United Farm Staff, different grassroots actions, and political campaigns earlier than returning to Cambridge to complete his undergraduate and graduate levels. Whereas hardly a straight line, Ganz’s profession trajectory from activist to organized-labor scholar follows a sort of logic rooted in his childhood because the son of a rabbi and a trainer who imparted lasting classes about race, equality, and social justice.

“I consider him because the Rabbi of Organizing,” stated Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Authorities and Sociology, who was Ganz’s Ph.D. adviser and is now a colleague and buddy.

“Marshall has helped to coach lots of the organizers who’ve labored for a few of the main political campaigns. [He] teaches folks the way to relate to others, the way to construct organizations, which doesn’t come naturally to at this time’s younger, and the way to harness ethical ardour for collective objective.”

Ganz’s mom, who was raised in Virginia, studied philosophy and psychology on the Faculty of William & Mary. His father enlisted within the U.S. Military as a chaplain in 1944, a 12 months after Ganz was born and the final 12 months of World Struggle II.

The younger rabbi was despatched to Germany to serve American GIs, however, after the tip of the warfare, a lot of his work concerned Holocaust survivors. He was joined in Germany by his household in 1946, they usually lived there for 3 years.

It was a tough time that left a long-lasting impression on Ganz, whose fifth birthday celebration was held in a displaced individuals camp for youngsters who’d been orphaned within the warfare. He was to offer presents somewhat than obtain them.

“My dad and mom interpreted the Holocaust to me as not being merely about anti-Semitism, however about racism very explicitly,” stated Ganz. “My mother, coming from the South, was so clear about it.”

After rabbinical posts in Washington, D.C., after which, Fresno, California, the household settled farther south in Bakersfield, the place Ganz lived via highschool. A scorching, dry metropolis of farms and oil rigs (and “outlaw” nation music superstars Merle Haggard and Buck Owens), Bakersfield was not the place a youngster who admired the Nineteen Fifties Beat Technology writers in San Francisco noticed himself long-term. Regardless of having a racially and ethnically various inhabitants, Ganz stated, “It stays in all probability some of the racist cities in California.”

At his mom’s urging, he set his sights on Harvard Faculty regardless of by no means having been to Boston.

“I solely utilized right here, which was extra silly than smug,” he stated. Ganz was driving a supply van for a Chinese language restaurant part-time as a highschool senior when he acquired the letter that he had gotten in and extra importantly, acquired a scholarship. “In any other case, there’s no manner I may have come.”

Ganz arrived at Matthews Corridor as a first-year within the fall of 1960, simply because the intently contested presidential race between Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Sen. John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts was reaching a crescendo.

Simply weeks after Kennedy’s victory, the brand new president-elect visited Harvard Yard to have fun and was later joined by college and directors together with economist John Kenneth Galbraith and McGeorge Bundy, then dean of the School of Arts and Sciences.

“It felt like, the entire sudden, you’re on this place the place historical past is going on,” Ganz stated. “This proximity to historical past was actually highly effective.”

That pleasure was tempered, nonetheless, by the difficulty Ganz was having discovering his social and mental area of interest.

“There have been all these guys in tweed jackets that went to colleges that I had by no means heard of — Andover, Exeter — they usually all appeared to know the school by their first identify,” he stated.

Ganz had hoped to affix a brand new social research program began by the famend political scientist Stanley Hoffmann. “However I didn’t get into social research, and I didn’t know fairly what to do,” he stated of his sophomore 12 months. So, he studied authorities however discovered it unengaging.

“I used to be within the relationship [between] tradition and politics. That’s what I used to be actually drawn to — however that wasn’t a division,” he stated.

Ganz took off the 1962-1963 tutorial 12 months to reside in Berkeley, California, the place his girlfriend was learning theater. He acquired a day job at an insurance coverage firm, audited night time courses on the College of California, explored town’s people and rock music scene, and considered what he needed to do along with his life.

A collection of occasions in 1963 began bringing issues into focus for Ganz. It started with the assassination of NAACP activist Medgar Evers by a white supremacist in June. Later that summer season 250,000 folks joined Martin Luther King Jr. for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. In September the Ku Klux Klan bombed the sixteenth Road Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing 4 younger Black women.

Ganz returned to Harvard that fall, altering his focus to Historical past and Literature (he deliberate to put in writing about Bertolt Brecht, the Berliner Ensemble, and Weimar Germany). Quickly after he was recruited by Civil Rights activist Dottie Zellner to affix the Associates of SNCC (Scholar Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), working from an workplace within the basement of Epworth Methodist Church close to the Legislation Faculty.

The SNCC was a gaggle of younger, brave, largely Black school college students who organized peaceable protests and voter drives in Southern states. It was chaired by John Lewis, later a Democratic congressman from Georgia. Via his involvement with the SNCC Ganz started spending time with like-minded spirits in Cambridge and numerous organizers.

Ganz and others had been invited to go to SNCC headquarters in Atlanta so they may return to prepare strain on Harvard which, it turned out, owned inventory in Mississippi Energy and Gentle.

“We didn’t win that one,” he stated, “however the extra I did, the extra dedicated I turned.”

That spring a coalition of Civil Rights teams, led by the SNCC, determined to launch a Freedom Summer season venture to help the work of Black organizers and group leaders in Mississippi. With these activists underneath fixed assault and arrest, the SNCC strategized that Southern legislation enforcement would possibly assume twice about going after college students from elite faculties and universities within the North.

Volunteers, together with Ganz, had been repeatedly arrested, harassed, or crushed. Activists Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner had been kidnapped and murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan in rural Mississippi in June.

Ganz’s mom was torn about her son’s choice to journey South. Whereas she firmly agreed with the stand he was taking, she feared for his security. Ganz was headed to McComb, Mississippi, in Pike County, a hotspot of Klan violence. Greater than a dozen church buildings and different buildings had been bombed in spring and summer season of 1964, and a home the place 10 SNCC volunteers had been staying was dynamited.

“And so, for her, I used to be doing an excellent factor,” stated Ganz. “However she was scared and possibly ought to have been scared. ‘You may assist extra by changing into a lawyer’ — that was sort of the road. However I stated, ‘No, I’ve to do that now.’” She would quickly develop into an organizer of a Associates of SNCC group in Bakersfield.

The visiting college students helped efforts to prepare the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Occasion as a part of a plan to unseat and substitute the segregated state social gathering with their members on the nationwide conference in Atlantic Metropolis.

The plans had been thwarted by President Lyndon Johnson, who was operating for re-election, however the groundwork was laid for an additional spherical of organizing, culminating with the Selma to Montgomery March and, lastly, passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“It’s actually there that I discovered what was going to be my calling for the remainder of my life,” stated Ganz. “With all due respect to Harvard, my training about race, energy, and politics in America started there.”

That August, Ganz wrote to Winthrop Home directors telling them he wouldn’t return for his senior 12 months.

“I used to be taking part within the work of enabling folks to search out their voice, their solidarity, and their braveness to construct their very own energy to problem the racist energy being exercised over them. It was actual. It was about deep change. And it was working,” he stated. “I’m going to return and write about Weimar Germany? Why would I try this?”

Ganz remained within the South with SNCC for an additional 12 months earlier than returning residence to Bakersfield, the place he met Cesar Chavez and others who had fashioned a Farm Staff Affiliation in 1962 to prepare Mexican immigrants employed in fields and orchards of California. In 1965, the group would launch what would develop into a landmark five-year strike of Mexican and Filipino pickers generally known as the Delano Grape Strike.

“I had grown up within the midst of the farmworker world, however I hadn’t seen it, till I returned with ‘Mississippi Eyes.’ Right here was one other group of individuals of shade, additionally with out political rights, additionally with out safety of the labor legal guidelines from which they had been excluded, and California with its personal wealthy historical past of racial domination starting with the Native folks, the Chinese language, the Japanese, the Filipinos, and, after all, the Mexicans. So, I discovered Mississippi was not an exception to America. It was an instance of the America we would have liked to alter.”

[ad_2]